Lunchtime Lecture: 3 Things About Chicago River Bridges

Author Partrick McBriarty at the McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum

Author Partrick McBriarty at the McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum

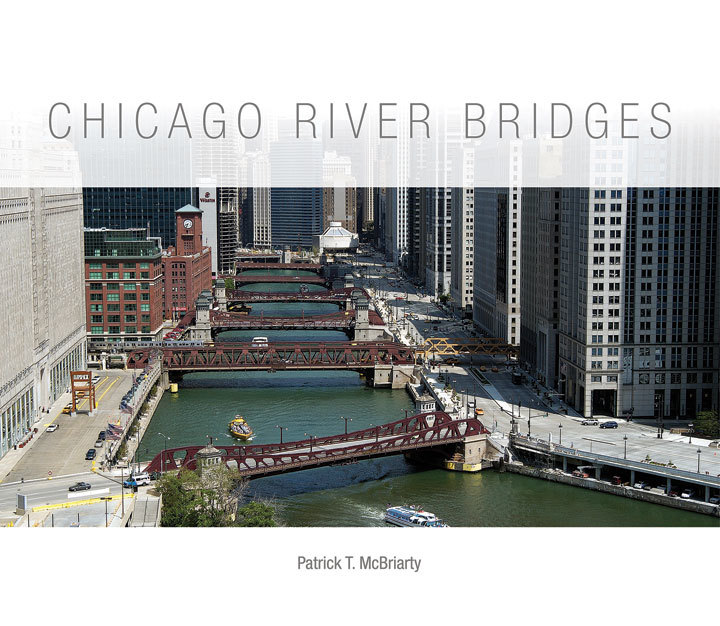

The fascinating history of Chicago River bridges was the subject of the final scheduled Lunchtime Lecture of the season at the McCormick Bridgehouse and Chicago River Museum on Aug. 26. “As a bridge nerd, I love historic bridges. And if they’re moveable, to me, it’s like playing with Tonka trucks,” said historian , author of “Chicago River Bridges” and co-host of the .

Here are three things you may not know about Chicago’s bridges from McBriarty's talk:

1. Today, most of the boat traffic on the river is pleasure craft and that limits the number bridge lifts. In the spring, the bridges downtown rise to allow the boats to move from storage downstream to Lake Michigan. In the fall, the boats return. But when the Michigan Avenue bridge 第一吃瓜opened in 1920, it probably lifted and lowered about 2,000 times in its first year, McBriarty said, because of the amount of commercial traffic. “There was a joke at the time that when you were late to a meeting it was said you ‘got bridged,’ “ he said.

Boat owners do not pay fees for the bridges to lift as they are designated navigable waterways, said McBriarty.

2. A 1992 incident narrowly missed killing a bridge maintenance worker when an enormous iron ball flew from a crane and tore into his car through the driver’s side back window. The worker, as Jesus Lopez, was in the car at the time. “I guess I was just lucky,” Lopez later told reporters of the close call.

The incident occurred when a leaf of the bridge suddenly sprang up during a rehabilitation project, sending a construction crane crashing down and the iron ball hurling into Lopez’s car. Six people on a nearby CTA bus were also injured in a panic when debris came raining down on the bus. Two traffic light poles, a crossing gate, and a Chicago police car were also damaged. Vibrations in the bridge, perhaps caused by wind, may have caused the leaf to violently spring upward, with the crane serving as a counterweight, according to a Tribune report. “It flipped 第一吃瓜open like a catapult,” said McBriarty.

The worker, he said, “stepped out apparently unscathed but a little shaken up.”

3. Another near-catastrophe occurred on the day the bridge noisily debuted in 1920.

“It was a huge deal. They had a big parade. There were bands. They had different groups parading through,” he said. Sometime during the ceremony, a tug boat pulled up and tooted its horn to request that the bridge be lifted.

“The bridge tender followed the procedure, which was to make sure there was nobody on the bridge, close the traffic gates and then raise the bridge,” he said. “This being a double-decked bridge there was a problem: nobody made sure the lower level was cleared.”

About five cars were still on the bridge below as the bridge prepared to lift. The noise from the celebration drowned out people shouting for the bridgetender to stop and he could not hear the warnings. Quick-thinking policemen shot their pistols into the air which got the attention of the bridgetender.

“The gunfire averted this disaster of people getting killed,” McBriarty said.

Author Patrick Briarty is introduced by the 第一吃瓜's Director of Strategic Initiatives Joanne So Young Dill. The Lunchtime Lecture, normally held on the McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum plaza on the Chicago Riverwalk, was moved indoors because of rain.

McBriarty's book is available at the McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum in the bridgehouse on the southwest corner of the Michigan Avenue bridge or